When Nova Scotia declared a state of emergency of March 22nd, 2020, all parks, trails, and beaches in the province closed. These were early days, when cases were low in the province, and it was yet unknown how the COVID-19 virus would impact Nova Scotia. As the days went on, Stephen McNeil, Nova Scotia’s premier, feared that Nova Scotians were not taking the pandemic seriously. During a press briefing, the premier sternly advised Nova Scotians to “stay the blazes home”. People who disobeyed and ventured onto trails and into parks were fined. To ensure compliance, parks, trails, and beaches were wrapped in caution tape and surrounded by park closure signs. This signaled that parks were dangerous; a place where someone may contract COVID-19.

Parks are an essential public space for gathering, self-reflection, and physical activity; the mere act of being in nature promotes feelings of peace and serenity. In fact, there is a significant body of scientific literature outlining the health and well-being benefits of spending time in nature, particularly during periods of stress and disruption [2–5]. Research on the biophilia hypothesis reveals that humans have an innate tendency to connect with nature and by doing so experience mental and physical health benefits.

Why, then, were parks closed during this period of crisis? Surely it was possible to maintain access to parks in a way that aligns with public health guidelines…?

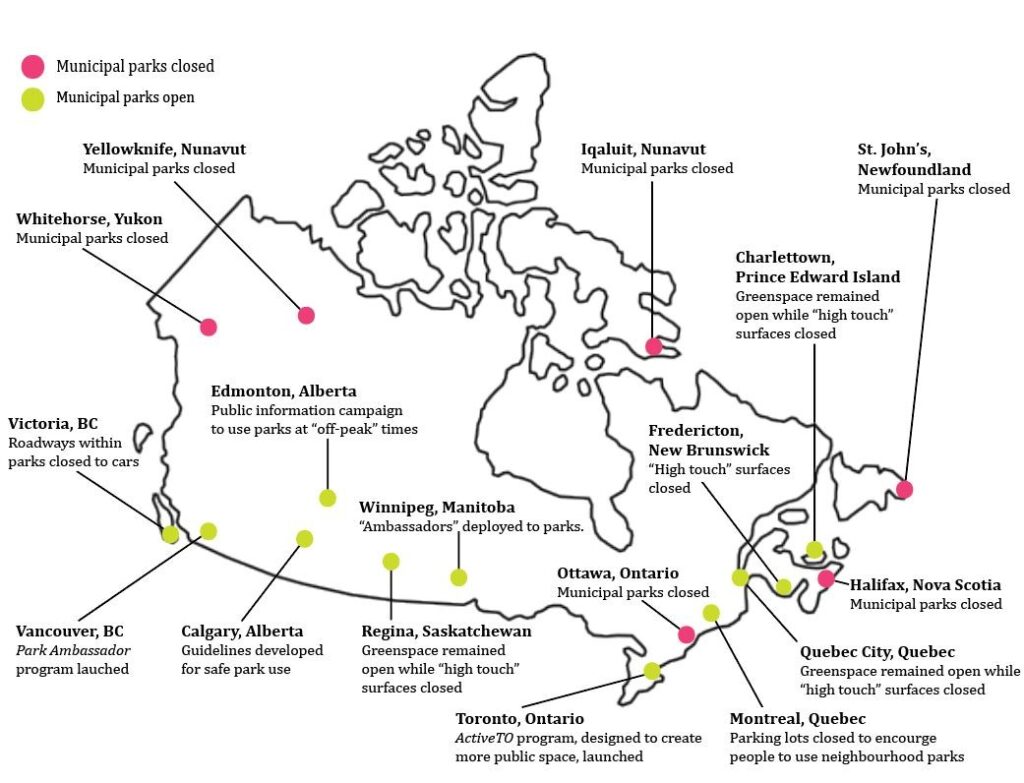

In order to understand how jurisdictions across Canada addressed the issue of park access, our research examined the actions taken by 17 major urban municipalities. Out of the 17, only six closed municipal parks to the public.

It turned out Halifax was an anomaly in its approach to park access during the COVID-19 crisis. Instead of seeing parks as a vector for COVID-19 transmission, most Canadian municipalities took action to maintain park access in a way that aligns with public health guidelines. On the other hand, all municipal parks, including pathways, public facilities, and playgrounds were closed in Halifax.

The map below shows the actions taken by municipalities to facilitate access to nature during the COVID-19 crisis and where in Canada parks were closed. Specifically, some municipalities simply closed “high-touch” zones, such as playgrounds, washrooms, and picnic tables, whereas other municipalities took a more active approach, deploying park staff, developing educational campaigns, and closing roadways in and adjacent to parks to create more room for park users.

Maintaining access to parks is an important component of any public health strategy for maintaining mental and physical health over the long-term and should be included in COVID-19 response policies. In fact, many government leaders touted the mental and physical health benefits of spending time in nature. For example, the manager of the Vancouver Park Board stated:

“We recognize the important role that our outdoor spaces play in people’s overall health and wellness, particularly mental health at this very stressful time”

– Manager, Vancouver Park Board (April 4th, 2020)

Furthermore, British Colombia Provincial Health Officer said:

“I do believe, and I’ve said this repeatedly, how important it is for us to have access to outdoor areas, particularly in urban areas where people being cooped up inside can lead to a lot of other anxiety and challenges and problems, including mental health problems”

– Dr. Bonnie Henry (April 22nd, 2020)

Finally, despite a six-week park closure, Nova Scotia’s premier also commented on the health and well-being benefits of park access. When announcing the opening of provincial and municipal parks on May 1st, 2020, Nova Scotia’s premier stated:

“Get out, get fresh air, do a little physical activity and hang [out] with your family. It’s the best medicine right now”

– Stephen McNeil (May 1st, 2020)

The way in which government officials framed the issue of park access, that is, as a way to support mental and physical health throughout the pandemic, makes a case for maintaining access to parks during crisis.

There is a growing body of research that suggests the risk of contracting COVID-19 in an outdoor environment is low [8]. This fact suggests that it is possible to maintain access to parks throughout the COVID-19 crisis, particularly if extra safety precautions are put in place. For example, many municipalities closed “high-touch” zones within parks. This included playgrounds, picnic areas, and washrooms. Another common strategy was to deploy municipal staff to disseminate information about the importance of physical distancing. Instead of taking an enforcement approach through increased policing and ticketing, which arguably creates more stress and division within a community, education promotes safe behavior within parks. Finally, closing roadways within or adjacent to parks was another common strategy intended to facilitate safe park use. Toronto’s ActiveTO program, for example, identified opportunities to expand public space by closing roadways thereby promoting physical activity and facilitating access to nature, even within a dense urban environment.

The health and well-being benefits of facilitating access to greenspace, particularly through periods of crisis, is supported by the concept of urgent biophilia, which posits that during periods of crisis, the desire to connect with nature is heightened. In fact, there are many examples of people seeking out contact with nature during crisis, including in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, in refugee camps, and following the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre [5]. In each of these examples, connecting with nature aided the affected community’s recovery efforts by supporting mental and physical health. COVID-19 will likely be no different. By developing strategies aimed at facilitating access to nature during crisis, the capacity for both individuals and communities to navigate social and economic challenges will be strengthened.

While COVID-19 is a pressing public health emergency, other components of health, such as mental health and physical fitness, must not be ignored. In order to promote health over the long-term, opportunities for individuals to safely connect with one another, exercise, and enjoy the natural world should be prioritized. COVID-19 will likely be with us for the foreseeable future. By ignoring these components of health, we risk unleashing a slew of secondary health challenges, such as depression, addiction, and anxiety. By taking proactive steps to facilitate access to nature during a disaster, populations will ultimately be better prepared to navigate the social and economic challenges of the crisis and will experience more overall positive health outcomes.

The results presented in this article are a part of the research project: Access to parks during the COVID-19 crisis: Building resilience through urgent biophilia.

Please contact sashamosky@dal.ca for more information.

1. Groff, M. Parks, trails and driving ranges reopen as province eases some restrictions (update) – HalifaxToday.ca Available online: https://www.halifaxtoday.ca/coronavirus-covid-19-local-news/parks-trails-and-driving-ranges-reopen-as-province-eases-some-restrictions-2316867 (accessed on Jul 15, 2020).

2. Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305, doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.012.

3. Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kagawa, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9, doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.005.

4. Kellert, S.R.; Calabrese, E.F. The Practice of Biophilic Design; 2015;

5. Tidball, K.G.; Krasny, M.E. Greening in the Red Zone Disaster, Resilience and Community Greening; Springer, 2014;

6. Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Macassa, G.; Giusti, M. Urban nature as a source of resilience during social distancing amidst the coronavirus pandemic. 2020.

7. Tidball, K.G. Urgent biophilia: Human-nature interactions and biological attractions in disaster resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, doi:10.5751/ES-04596-170205.

8. Mackinnon, B.-J. Higgs says municipal parks can stay open if physical distancing enforced | CBC News Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/covid-19-municipal-parks-higgs-new-brunswick-1.5518558 (accessed on Jun 9, 2020).

9. Grochowshi, S. Stick to your local parks this Easter weekend, says Metro Vancouver – Maple Ridge News Available online: https://www.mapleridgenews.com/news/stick-to-your-local-parks-this-easter-weekend-says-metro-vancouver/ (accessed on Jul 24, 2020).