This fall, I chose to look at wayfinding systems in downtown Halifax as part of my coursework at Dalhousie’s School of Planning. Wayfinding systems are put in place to make cities easier to navigate for people of all ages and abilities. My project started looking at how a wayfinding system could enhance the tourist experience in downtown Halifax. However, a wayfinding system would benefit both tourists and locals alike, making the built environment more accessible for everyone.

Unlike many cities of a similar size, Halifax does not have a wayfinding strategic plan. This means that there is little to no informational signage directing people to destinations and facilities around the downtown. Moreover, the signage that currently exists is primarily located around the waterfront, targeted at tourists rather than residents, and has limited function for accessibility.

A current example of a wayfinding sign in downtown Halifax. This sign shows North-South directions, directing people towards tourist destinations along the waterfront. This sign does not reflect any element of accessibility.

My research found that there is great potential for the implementation of a wayfinding system in Halifax. Wayfinding in Halifax could encompass a combination of physical signage, sidewalk design, or any other audio-visual cue that could help an individual navigate the built environment. While municipal plans such as the Active Transportation Priorities Plan and the Land Use By-law and Transportation and Streetscape Design Functional Plan outline the need for a wayfinding strategy, there is currently no other publicly available document to explicitly address wayfinding in downtown Halifax.

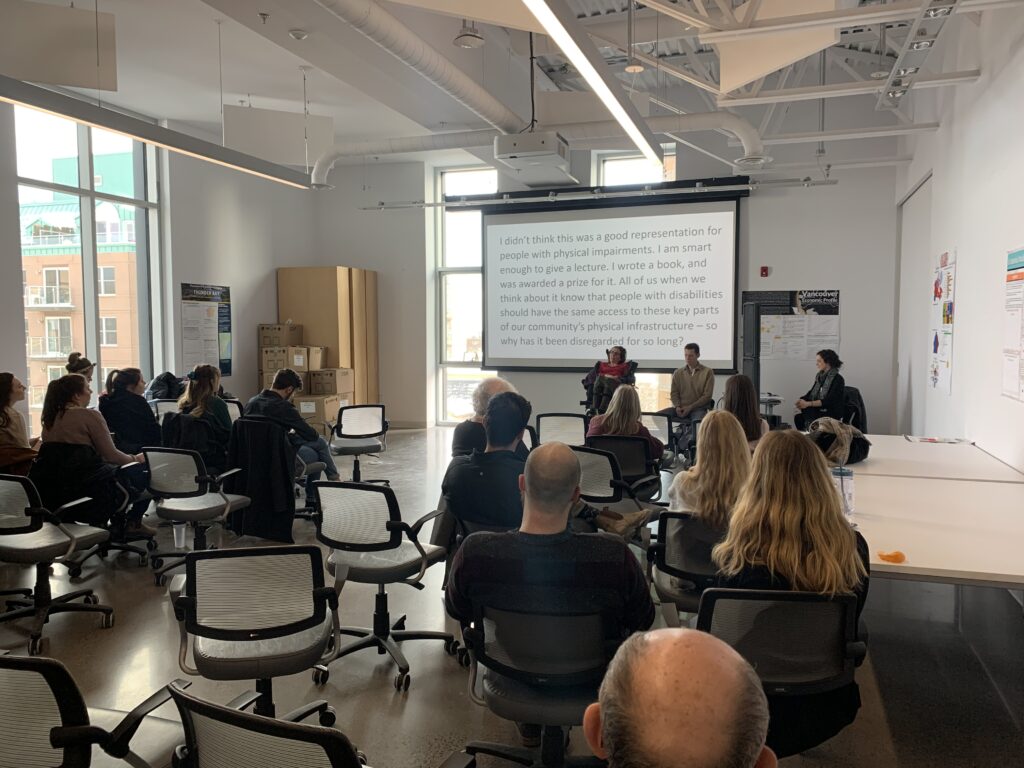

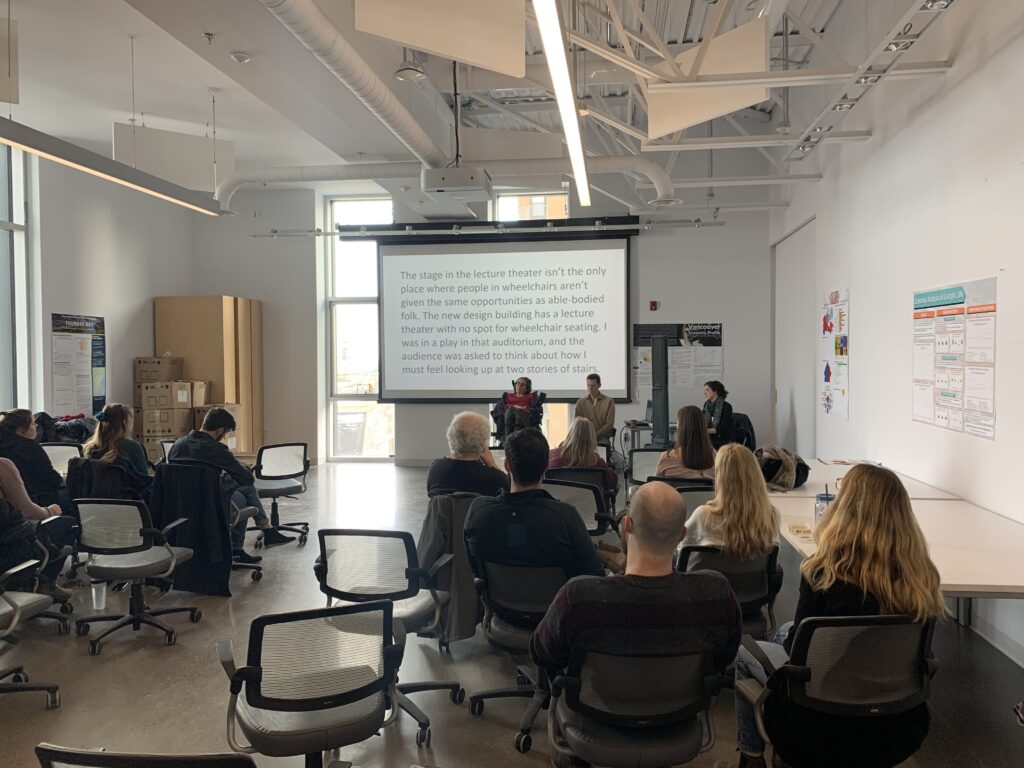

While I was looking into wayfinding, I attended a lecture by Andrew Taylor, an accessibility advocate who spoke about his experience of Halifax’s downtown from his perspective as a person with a physical disability. Andrew shared some of the challenges he faced when navigating due to lack of signage and information relevant to his accessibility needs. For example, because there is no information suggesting to users which streets and/or areas of the city have accessibility features or facilities, Andrew said he had to be very particular about which routes he traveled and where he chose to go. Andrew added that he often felt like he could only travel on streets he was already familiar with. A universally accessible wayfinding system could direct users to accessible washrooms, building entrances, ramps, and/or routes that have been designed for accessibility in order to address this concern and enhance the experience of individuals living with a disability.

Andrew’s talk made me reconsider what is meant by a good wayfinding system. While traditional wayfinding systems have an explicit focus on informational signage, there are a variety of ways that directional information can be integrated into the built environment. Design interventions in the built environment, such as auditory signals at an intersection, ultimately create a safer urban environment for everyone. Another example of how this could be done is by implementing visual cues that alert individuals of an upcoming curb. This would in turn make more areas of the city accessible to residents living with a disability.

Halifax is a great candidate for a wayfinding system to assist tourist and locals of all abilities to effectively navigate and experience the community. If Halifax were to implement a wayfinding system, applying an accessibility lens to the design is crucial. Designing a wayfinding system through an accessibility lens means understanding how people with disabilities move through the city. This must be done through careful consultation and documentation of the lived experience of those in the disability community. Capturing how people with disabilities experience downtown Halifax is a critical first step in building a wayfinding system that benefits all people.