A three-part series looking at accessible housing in Canada and Nova Scotia (2/3)

Made official in 2017, Canada’s National Housing Strategy (NHS) is a 10-year, $72 billion dollar plan comprised of various programs and funding streams that intend to “create a new generation of housing in Canada” that is “sustainable, accessible, mixed-income, and mixed-use”. A central goal the NHS is to address the housing crises being experienced in many cities and regions across Canada, which are largely characterized by significant shortages in affordable housing stock and increasing homelessness.

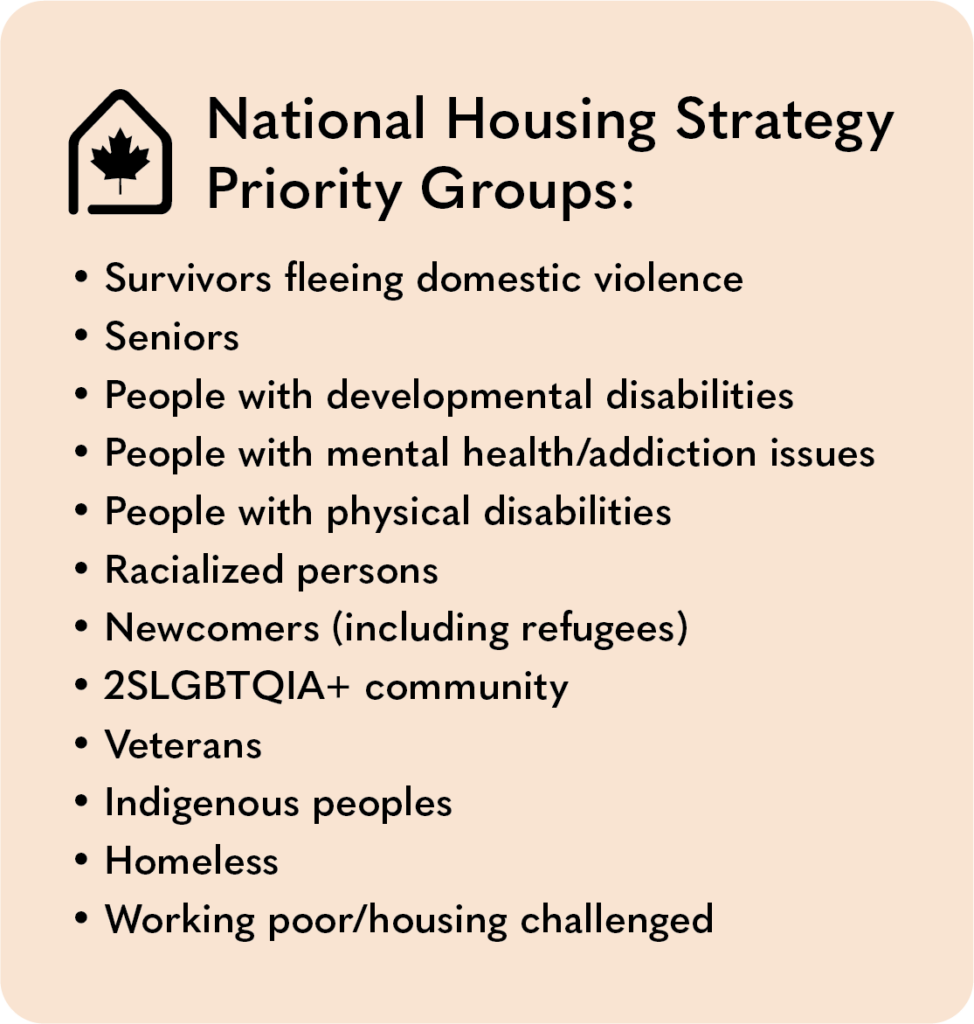

Since its inception, the NHS has aimed to improve housing outcomes for a number of “priority groups” that it classifies as vulnerable. Of these groups, several have housing needs that go beyond the traditional housing standards of affordability, adequacy, and suitability – often requiring that housing is accessible. NHS priority groups that may need accessible housing include people with physical disabilities, people with developmental disabilities, and seniors. At its outset, the NHS recognized that Canadians with disabilities face a host of difficulties in accessing housing that is not only affordable but appropriate for their needs, which it vowed to address by improving accessibility in housing units across the country.

While this commitment to improving housing outcomes for Canadians with disabilities was welcomed news, important questions still loomed: how many accessible housing units were going to be built through NHS programming, and how? Would the NHS be able to significantly alleviate Canada’s need for accessible housing units?

In terms of targets for accessible housing units to be constructed, two significant numbers were put forward: the NHS would build 2,400 new housing units for Canadians with developmental disabilities and 12,000 new affordable units for seniors, both through the National Housing Co-Investment Fund. As of the December 2022 NHS Progress Report, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) reported that 845 new units for people with developmental disabilities are at the “commitment” stage, as are 5,925 new units for seniors. However, it is important to note that data pertaining to accessible and affordable units currently under construction or that have been successfully built as a result of the NHS has not yet been provided. Perhaps even more importantly, the relationship between the targets that were set and an identified need for accessible housing units is unclear.

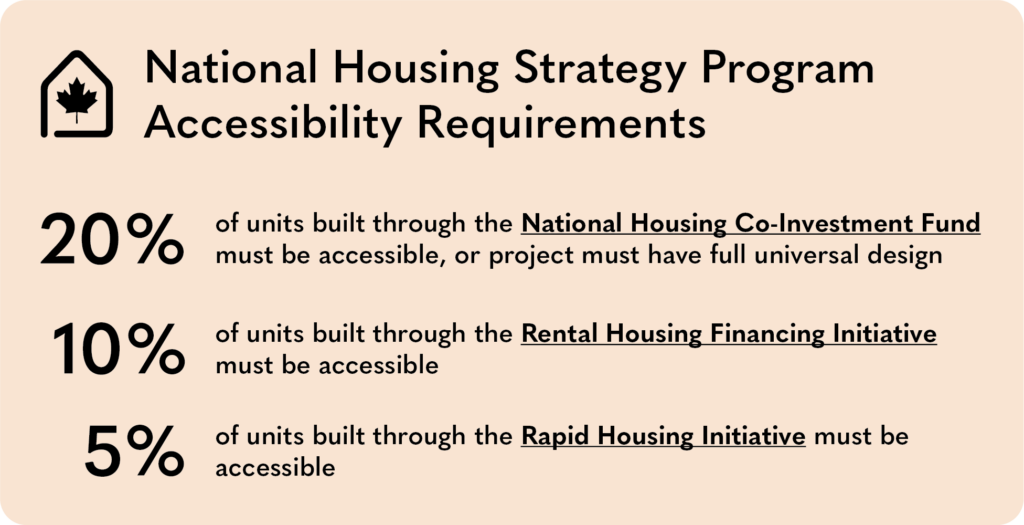

Along with the National Housing Co-Investment Fund, the Rental Construction Financing Initiative and the Rapid Housing Initiative make up the three NHS programs receiving the highest levels of funding, all of which are focused on the construction, renewal, and repair of housing units. These three programs feature another way in which the NHS addresses Canada’s need for accessible housing: project accessibility requirements.

In short, these requirements aim to ensure that any project receiving funds through these programs must, to some extent, provide housing that can be considered accessible. For instance, the National Housing Co-Investment Fund gives developers the choice between (a) ensuring 20% of a project’s units are accessible and has barrier-free common areas, or (b) ensuring the entire project has full universal design. Similarly, the Rental Construction Financing Initiative (10%) and Rapid Housing Initiative (5%) require that a portion of units within a project are accessible. While thousands of units are being built, renewed, and repaired through these three programs, there is no reporting in any case as to whether these accessibility requirements are being met.

Together, limited progress reporting on targets for priority groups and the absence of reporting on program accessibility requirements leads observers to question the NHS’ ability to address Canada’s need for accessible housing. It would certainly be beneficial to know how many of the 15.9% (950,000+) of Canadians with disabilities found to be in core housing need in 2017 no longer classify as such as a result of NHS programming. This, however, is not yet known, and may not be until data from the 2022 Canadian Survey on Disability is released.

As the NHS passes the halfway point of its lifespan, it may be an appropriate time to reconsider how it has addressed the need for accessible housing to date. For starters, it would be beneficial if the targets that were set for priority groups in need of accessible housing were clearly tied to an identified need. Whether 2,400 new units for individuals with developmental disabilities and 12,000 new affordable units for seniors will make a significant dent in alleviating housing needs for either of these groups goes is not something that is addressed by the NHS. Undertaking a type of needs assessment for accessible housing that identifies how many accessible housing units are needed (and for which specific priority groups) could allow the NHS to reset its targets and re-calibrate its programs and initiatives to better meet the country’s need for accessible housing. In addition to setting better targets, the NHS could also benefit from improving its progress reporting. Going into further detail about how many accessible housing units have actually been built as a result of NHS programing and how this has alleviated needs could serve to enhance transparency and accountability within the NHS.

To continue this exploration of accessible housing in the age of the NHS, the next blog in this series will take a look at the situation in Nova Scotia – a province that has long needed to see progress made in the area of accessible housing.

Further Reading

CMHC. (2018). Priority areas for action. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/nhs/guidepage-strategy/priority-areas-for-action

CMHC. (2019). Identifying Core Housing Need. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/professionals/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/core-housing-need/identifying-core-housing-need

CMHC. (2022). Progress on the National Housing Strategy: December 2022. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/place-to-call-home/pdfs/progress/nhs-progress-quarterly-report-q4-2022-en.pdf?rev=60eda13a-fc61-4bfe-ab46-043ef9fe12dd

CMHC. (2023). What is universal design? Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/blog/2023/what-is-universal-design

Government of Canada. (2016). Canada’s National Housing Strategy. https://www.placetocallhome.ca/what-is-the-strategy

Randle, J., & Thurston, Z. (2022). Housing Experiences in Canada: Persons with disabilities. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/46-28-0001/2021001/article/00011-eng.htm

About the Author

John Gamey (MPlan) graduated from Dalhousie University’s Master of Planning program in May 2023. This blog series outlines some of the research he conducted in the area of accessible housing in Canada and Nova Scotia under the supervision of Dr. Mikiko Terashima.