Three washroom entrances labelled with human-sized icons for male, female, and universally accessible on each.

It has been an eye-opening experience when it comes to finding accessible public washrooms in Japan. Tokyo, in particular, has been making giant strides in making many public washrooms accessible over the past couple of decades. The Tokyo Olympic Games in 2021 also boosted the accessibility of the city. It seems that train stations, shopping malls, and tourist destinations have a healthy number of well-equipped accessible washrooms. It is currently mandated that there must be at least one accessible washroom unit in public facilities of 50 square meters (about 550 square feet) and larger.

Accessible washrooms in public spaces

The photos below show a washroom on one of the Toyo University campuses—where the Department of Life Design is located (yes, they research how to design accessible washrooms). Many of the public washrooms located in large buildings have a sink for ostomy (left) and an adult change table (right).

Washrooms in train stations, shopping malls, and major tourist destinations (e.g., famous shrines and temples) are often equipped with voice instructions which walk you through the process of using them: from which button to push to open the door, to locking the door, and even how to flush the toilet. Some even alert you to watch for slippery floors. Most of all, public washrooms are CLEAN! Apparently, some users spend time in them to eat lunch, read, and nap on the adult change table.

There seems to be a debate around able-bodied users ‘hogging’ accessible washrooms. However, Professor Yoshihiko Kawauchi, the author of the book, “Barrier-Free without Dignity” cautions judging persons who may have an invisible disability or have a particular privacy need. These accessible public washrooms have become a safe haven for many people. Professor Kawauchi posits that it is about having more washrooms that serve different functions for different needs, and not about making rules for who gets to use them.

Washroom signs

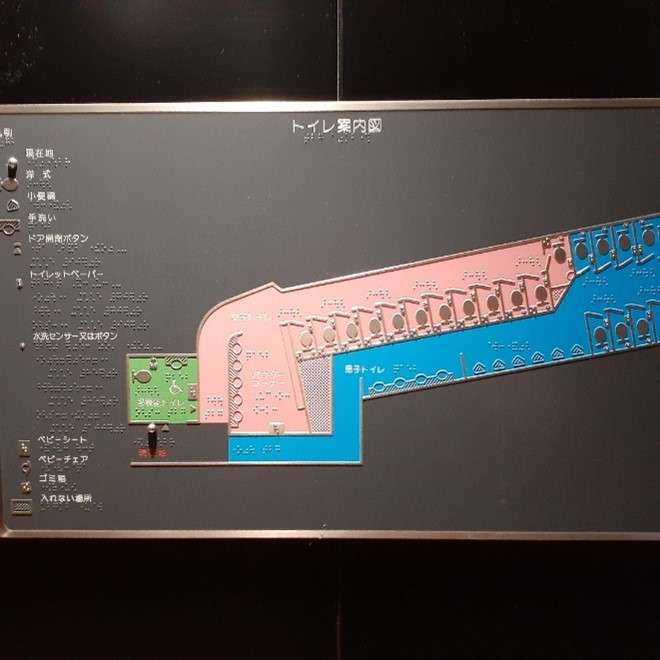

What is also striking is the signage. Signs for washrooms are large, clear, and detailed, and they are EVERYWHERE. These signs have become part of the aesthetics for busy public spaces, boldly telling you where to go and they are hard to miss. Many of the washrooms also tell you the layout of the washroom complex (often with tactile maps and braille), so that you can anticipate how you might need to navigate the space. Perhaps most important, these location maps almost always show where YOU are so that you can orient yourself before you make your move.

A tactile map on a black wall showing the floor plan of two multi-stall gendered washrooms.

The caveat

To be careful not to paint the picture of Tokyo as this super futuristic city with anything and everything tech-savvy and new, here is an example of ordinary public washrooms in places like neighbourhood parks and smaller shopping centres. There are more of these than what we see as ‘best practice’ examples on magazines and websites. There are still traditional ‘squatting’ style toilets all over the place, too, and they are a bit… well, shabby. These are likely to disappear as the places are renovated and new toilets are installed.

Attention to detail

Somebody must take great pride in designing public washrooms in Japan. Yes, there are some award-winning, fabulous looking washrooms designed by famous architects and designers in Tokyo.

But more mundane, everyday washrooms in busy train stations and shopping malls are also well thought-out. So far, I have yet to encounter a (non-squatting style) washroom without a heated seat and self-washing devices. Many functions are touch-less and with automated voice instructions. Some come with a place to hang your umbrella, shopping bags, and a little baby seat in bathroom stalls for moms (I wonder if the baby seats are installed in men’s washrooms?). Some come with fake toilet flushing sound to mask the ‘bathroom’ noise—this, I believe, was an invention to prevent people wasting water by flushing the toilet multiple times.

What is adequate?

Can we do it in Canada? Of course, we can. Would it be expensive? Absolutely. The question of feasibility is a tricky one. Governments must gauge the cost of making accessible public washrooms against other competing priorities that the public funds must stretch to meet. Like many other jurisdictions, Japan has also struggled with the question. It seems a tad easier in Japan because there is a ‘market’—if you build it, they will come (by hundreds of thousands every day). To the eyes of an outsider, there seem to be a lot of accessible washrooms wherever you go in Tokyo. On the other hand, Tokyo has 14 million people. How many is adequate for Tokyo? How many is adequate for smaller Canadian cities like Halifax? Who decides what is adequate? Can an optimal washroom-to-population ratio be established? At what population size would such a ratio become unfeasible due to economy of scale? These are the questions that may keep planners awake at night in Japan, Canada, and elsewhere.