Last spring, our team attended the national Navigation conference of the Canadian Institute of Planners. There, PEACH researchers and students talked with planners, engineers, development officers, and other built environment professionals from across Canada about their knowledge of accessibility standards and collected valuable feedback for a recently completed research project.

About the project

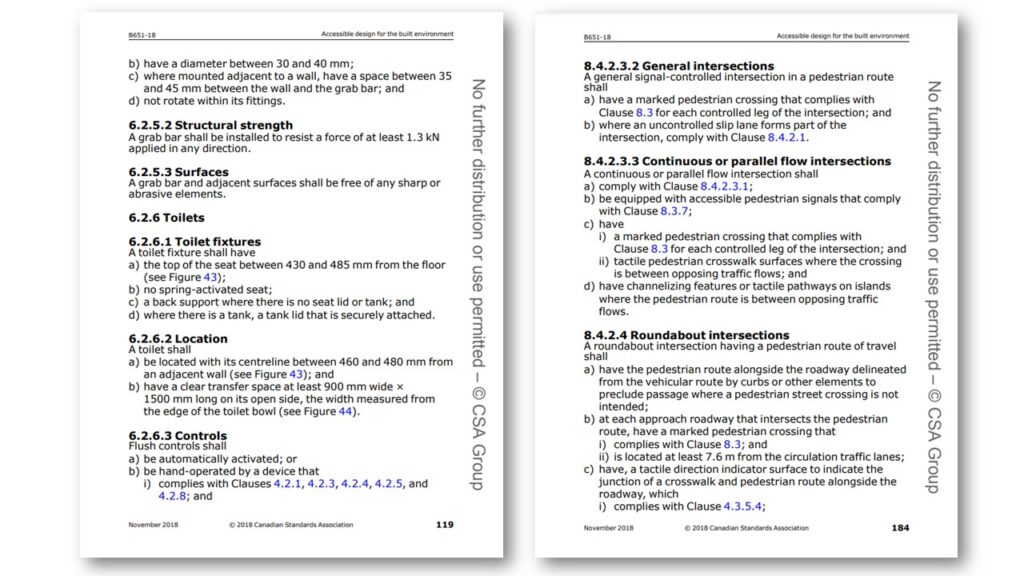

The project, called Visualizing Accessibility Standards: A demonstration with CSA B651, tested how the addition of visual aids (e.g., diagrams, images, and reference videos) to the CSA B651 standards text may enhance its use by professionals. The Canadian Standards Association’s (CSA) B651: Accessible design for the built environment is a regulatory document that prescribes minimum and maximum measurements and design requirements to make indoor and outdoor spaces accessible to more people – specifically, people living with disabilities. They contain specifications for doors, walkways, stairs, bathroom facilities and more in rows and rows of technical and jargon-heavy text. Attendees of the conference were quick to confirm that text-heavy regulatory documents like this one can be challenging to engage with.

What we heard

The subject matter of accessibility standards was often unfamiliar to the professionals we spoke to. While many felt they had some familiarity with accessibility needs, few had worked directly with accessibility standards before, as they were not yet required by their jurisdictions. When asked to read samples of the B651 text, many conference-goers appeared perplexed. Most had follow-up questions to ask our team, such as asking for additional details or context to fully understand the textual description. Overall, they were relieved to see the visual aids produced through the Visualizing Accessibility Standards research project, especially the three-dimensional (3D) models simulating accessible spaces, and videos featuring first-hand accounts of disability experiences.

Some key findings

We collected 552 pieces of feedback on the prototype visuals produced by this project and found these two types of visual resources to be the most well-received by professional audiences. Most professionals were attracted to the 3D models of spaces because they were recognizable as real space without having the clutter of photographed spaces. They found it helpful when the graphics showed a design component from multiple angles in a realistic context, and with measurements clearly applied to the imagery.

Narrative videos also received the most positive comments overall. In these videos, people with lived experience of disability spoke about design features from the standards, explained how they are applied in daily life, and described how the features impact their own experience of disability. Professionals liked that these videos explained ‘why’ the standards prescribe what they do. They also said that the explanation provided in the narrative videos was valuable for motivating implementation of the standards and demonstrating how following (or not following) the standards directly affected people’s lives.

In short…

Professions such as architecture, planning, engineering, building development and managing, construction, and others, have a significant impact on the buildings and public spaces we all use daily. It is important to grow accessibility knowledge within these fields to realize more accessible communities. The feedback collected through this research indicates that people who are currently using accessibility standards can benefit from visual and audio-visual resources to support their understanding of accessibility needs and solutions, and that there is a gap to fill in bringing knowledge of accessibility standards to many built environment professionals. This research also further emphasized that bringing people with lived experience of disability into these professions as professionals themselves and/or as expert advisors, has the power to motivate and inform better decision-making towards accessibility.

PEACH researcher showing a narrative video to a conference attendee.